What I'm into lately

I'm a simple man. I like to tinker with things.

Recently we received a long awaited upgrade – I'm talking decades – to our home internet situation. We had been on DSL provided by a well known telco, one so hated on that they rebranded themselves a few years ago without bothering to also improve the service. Their DSL was the fastest and most reliable service we could obtain where we live, but it was by no means fast, nor reliable.

So, after a decade of calling a local fiber provider to request a service extension all the way out here, and then another couple of years of watching them slowly extend service all the way out here, one day in Early November we got a 1gb symmetrical fiber connection to our house. It's great. I never notice it, and that is all I want from the internet line.

I had never really bothered upgrading the local network situation, because the service to the house was so poor that it would be wasted effort but now, that is no longer true. So, I've been upgrading...

After a mis-start with an Open WRT router, I eventually just did the prosumer thing and bought a couple of Eero access points, because our fiber provider gave us an Eero gateway with the service and I figured I'd just go with it. I don't like that I am disallowed from changing say, the DHCP server that would let me set the pihole as local DHCP and block ads in the entire house, but at least it lets me set the pihole as the DNS server for the house. It's close enough, and does the job.

I bought an outdoor Eero unit to cover the yard and garage area where I'm working most of the spring and summer. The coverage was usually fine on the porch, but only a little way out into the yard it would fall off pretty hard. Now I have solid coverage all the way out to the garage, so what to do with that?

Smart home stuff

I was introduced to Home Assistant at my last job with Platform.sh. A couple of my colleagues ran HA and eventually I got curious. I'd pretty been anti-smart-home because my sense was that it was largely a ploy by big tech corporations that I mostly hate but still work with daily to further invade our homes and our privacy. Why else would Google buy Nest, and Amazon buy the Roomba company except to use them as data vacuums for the physical infrastructure that is your house? Yes, Amazon owns Eero, I know.

Anyway, HA is an open source smart home thing, so I figured “what the heck” and spent a little bit learning my way around it, albeit laboriously. This was maybe 18 months ago. The house's DSL finally died and we moved to a T Mobile cellular hotspot for the whole house in Sept-Nov while we waited for the fiber to be lit up, and the point is that I baiscally had to tear down the local network stuff that I'd set up before that because the T Mobile thing was seriously locked down. No way to use it except as the only wifi broadcaster, no way to run ethernet to a switch, for example.

So – come November and fiber to the house I decided to rebuild everything from scratch. This second time I had a much stronger mental model for how HA actually worked, which helped a lot. The other thing that helped a lot was installed Claude Code on the Raspberry Pi 4 that I was running HA on. I wanted a slightly more involved than vanilla HA setup, and so I was able to chat through the setup in a couple of hours a day with Claude. The setup is currently:

- HA running in Docker on

pifour.local - Metabase (for dashboarding) also running on

pifour.local - ESPHome also running on

pifour.local - Postgres for the HA backend, rather than the default SQLite database. I wanted this for making it easier to use with Metabase, which also use the Postgres instance as its backend as well.

- After a month or so of running all of this on the R Pi 4, I moved Postgres to a R Pi 5 that I have attached to the same switch in my office. Claude helped me set up replication to copying the data to the new instance, and then cutting it over to

pifive.localas the primary with no data loss.

- After a month or so of running all of this on the R Pi 4, I moved Postgres to a R Pi 5 that I have attached to the same switch in my office. Claude helped me set up replication to copying the data to the new instance, and then cutting it over to

This is all stuff I know how to do conceptually, but the time spent on googling and trial and erroring on it would've taken me much longer than my patience for getting to the end of it. Claude helped me do that Postgres migration to pifive.local in about ten minutes.

Sidenote – we had a power outage last week and not everything came back up as planned, because Postgres was on another machine and the startup dependency ordering in a little Docker compose file couldn't work across to another machine. Chatting with Claude about whether or not this was the problem that Kubernetes solves helped me understand K8s a little better – a tech I've mostly kept my hands off of in the last decade – and also to realize that it was total overkill for my little 2 host setup.

The real fun

Ok, so, last little bit on this for today – I like data and maybe in some other post someday I'll go into detail about why I'm so obsessed with electricity usage and heat pumps and other eco-tech. If I were going to drop technology right now, I would go into HVAC and insulation, just sayin.

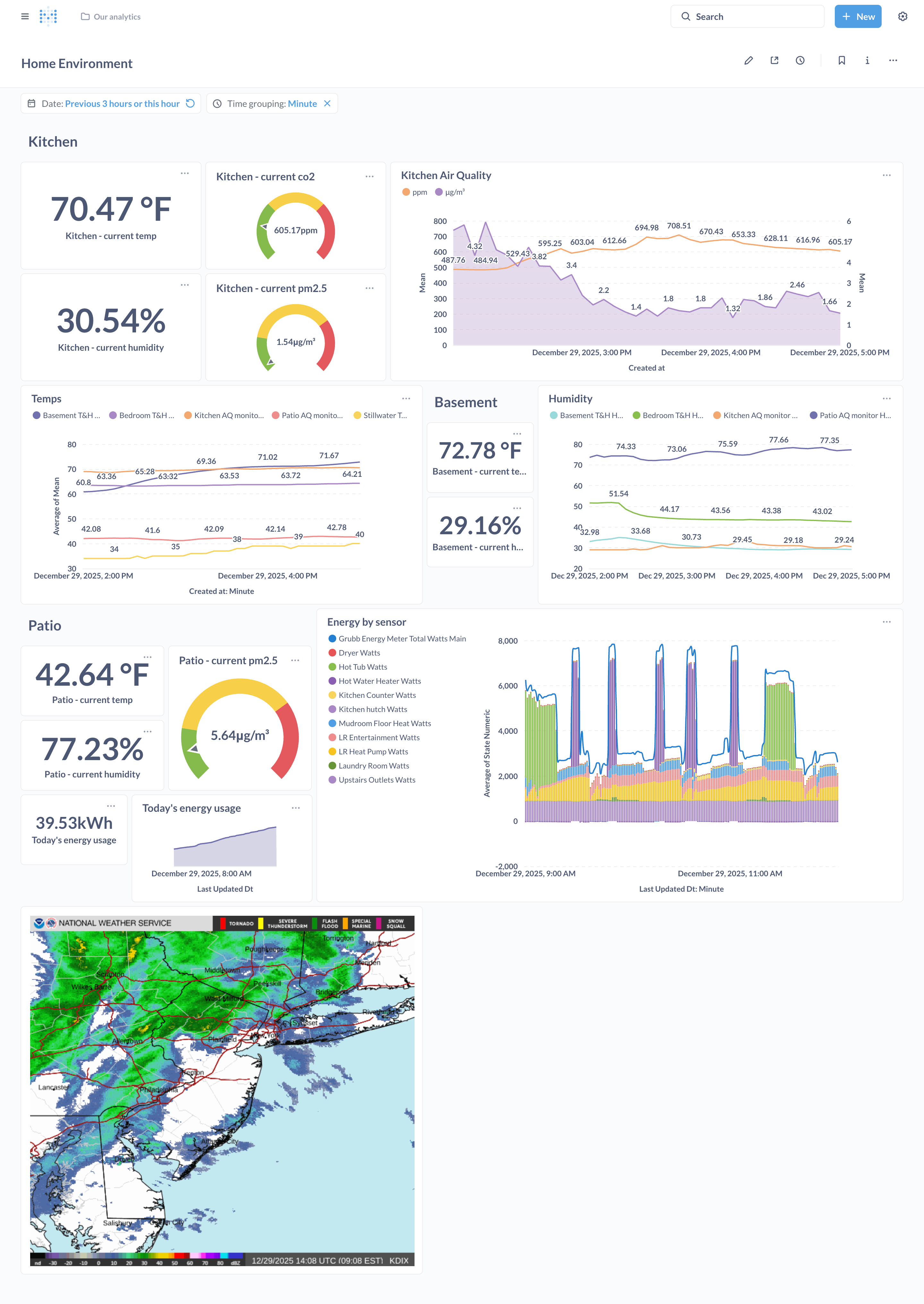

Anyway, my first time around I also bought one of those whole house electricity usage monitoring setups, the kind that you attach to each circuit in your breaker panel. I made a huge mess the first time because so many wires, but this time I went slower and much tidier. You can see that chart in this whole house dashboard that I've been working on for the last few weeks.